Value in Litigation & Implications for Litigation Finance

Executive Summary

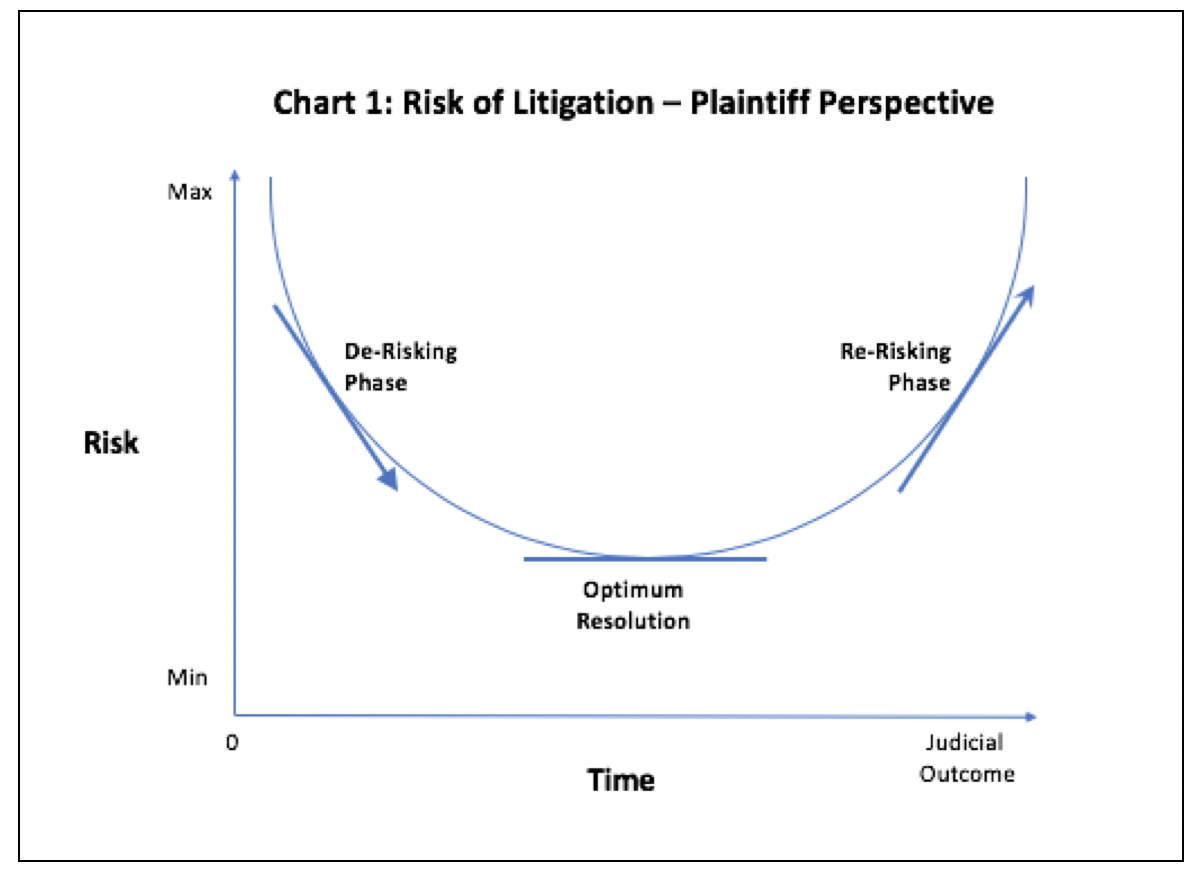

3 Phases of Risk:

De-Risking

Optimum Resolution

Re-Risking

Optimum risk-adjusted zone is when information is maximized and trial has yet to begin

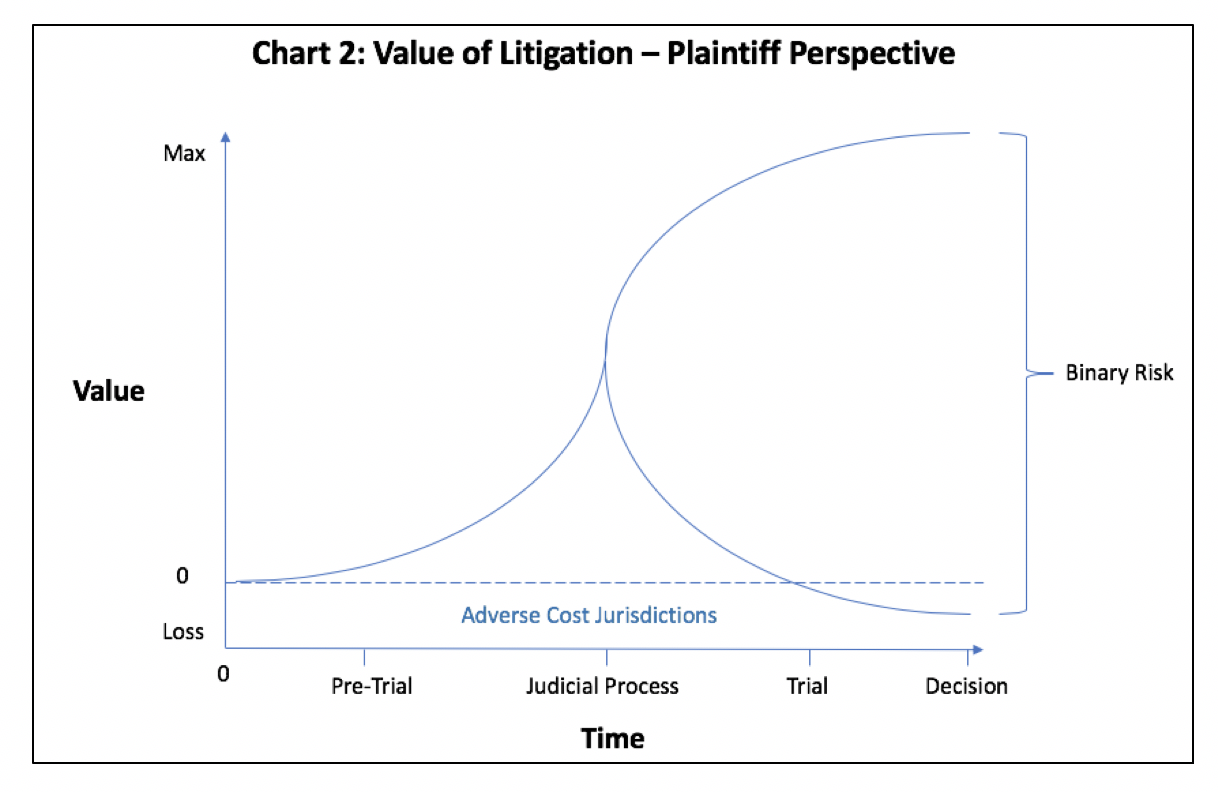

Once a trial begins, outcomes become binary in the absence of a settlement

Investor should assess quality of case resolution to ensure manager and portfolio does not exhibit excess binary risk

Diversification critical to investing in the litigation finance sector

Investor Insights

In assessing portfolio performance determine the extent of trial outcomes

Generally, a high percent of cases are settledAssess settlement performance in the context of industry settlement rates

Certain case types have lower settlement rates, so there is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach to analyzing portfolio performance

I was speaking recently with a local litigation finance manager about the concept of value of a piece of litigation in the context of litigation finance. As I thought more about the discussion and the implications for settlements and maximizing outcomes, I felt compelled to relay the thoughts in an article for other industry participants to consider and argue. Keep in mind that this is a simplistic view of a piece of litigation as most litigation has layers of complexity that influence valuation, not to mention precedents in other jurisdictions.

Value

The purpose of this article, however, is to discuss value. The intrinsic value of a piece of litigation is made up of a number of components that lawyers, plaintiffs and litigation fund managers assess as they underwrite their investment decision, which typically consist of the following:

merits of the case

collectability of damages

quantum of damages

justice considerations (judiciary and jurisdiction)

defense counsel effectiveness

defendant’s conduct re previous litigation

plaintiff counsel effectiveness

For purposes of this article we will mainly make reference to early stage pre-settlement cases.

Value is not a static concept in litigation. Nevertheless, litigation fund managers have to determine approximate value or a value range at the very early stages of a case when there is a relatively high degree of uncertainty, relatively few facts and little to nothing in terms of judicial proceedings. In the context of litigation, value varies with time (while time may add value in the short term by virtue of time contributing to the amount of information that can be gathered on the case, the longer a case drags on past the point where maximum information is available, the less valuable it is due to the time value of money), and proportionately, or perhaps disproportionately, with risk, which is in turn influenced by information. That is to say unknown data may come to light that becomes beneficial or harmful to the merits of your case and may influence its outcome &/or quantum. This may also include favourable judicial rulings that influence the outcome of a case. As an example, the ‘certification’ process of a class action in certain jurisdictions has a meaningful impact on whether the class proceeds with the action and ultimately is a strong determinant of success, typically through settlement.

Of course, in all jurisdictions the other big factor is access to capital so that plaintiff’s can finance the pursuit of their meritorious claims to the point of collection of damages – enter litigation finance. We will assume for the remainder of this article that all cases have the appropriate amount of financing (a significant assumption indeed).

As discussed, the value of a case is determined by two factors: risk and time . As illustrated in Chart 1, entitled Risk of Litigation – Plaintiff Perspective (courtesy of John Rossos, Bridgepoint Financial), all cases start on the left-hand side of the chart where risk is at a maximum, as there is relatively little information known about the case and hence a great degree of uncertainty about its outcome.

As plaintiff and counsel start to build their case and proceed through discovery, the case generally becomes ‘de-risked’ as the plaintiff team becomes more comfortable about the merits of their case and the quantum of damages. As we move toward the bottom of the semi-circle, we start to enter the zone of ‘optimum resolution’. However, ‘optimum resolution’ is not necessarily a value maximizing concept but rather a concept of risk-adjusted value maximization. The risk-adjusted aspect stems from the fact that both sides have about equal information concerning the dispute and are now able to make a rationale decision as to the possible outcomes and damage quantification. At the point where the process starts to go past the Optimum Resolution phase, the parties enter into a new phase of risk which is reflective of the binary risk (referred to as ‘Re-Risking’ in Chart 1) nature of litigation, whereby the outcome is determined by a third party judiciary.

In Chart 2, entitled Value of Litigation – Plaintiff Perspective, we look at the value of a piece of litigation relative to time. Consistent with Chart 1, as the plaintiff gathers more information regarding its case, the case generally starts to increase in value as risk diminishes. However, at the point where a judicial process commences (and assuming a settlement doesn’t occur between the start of the process and the decision), the graph bifurcates into two potential outcomes on the assumption that there is no resolution after the start of the trial - generally, either a win or a loss outcome. In certain jurisdictions where they have “adverse costs” or “loser pays” rules, the plaintiff will have to pay the defense costs and so there is a real financial cost in addition to the lost opportunity associated with a positive outcome.

Implications

The purpose of this analysis is to focus the plaintiff on the fact that on a risk-adjusted basis the zone of Optimum Resolution is the best point in the litigation process to resolve its case as it reflects the point of most knowledge and least risk. This is the point in time in the case to cast aside all of the emotional elements of the case and the impact of damages incurred and focus on a realistic outcome that can be achieved through negotiation and settlement, regardless of whether it makes the plaintiff “whole” or not. Of course , as the old saying goes “it takes two to tango”, and so if the defense is not of the same opinion or their analysis is skewed they may have a very different perspective on the appropriate amount on which to settle. In the case of insurance companies as defendant in cases, they may also have other considerations such as statutory reserve requirements or corporate strategic reasons to delay as long as possible (time value of money and the impact on their insurance reserves and investment returns). Nevertheless, the concept applies to both defense and plaintiff which is the reason underlying very high settlement rates in most litigation in all jurisdictions.

From an investor’s perspective, there should be a recognition that as each case in their portfolio extends beyond the zone of Optimum Resolution, the risk to their portfolio increases. Accordingly, if you are an institutional investor buying a secondary pool of litigation finance assets, you want to be sure you are not buying a series of old cases where the binary risk is high and you are not getting an appropriate discount to assume the risk. Of course, there are always exceptions to this rule. The reason a case has extended for a long period of time may be because the plaintiff has had successive wins at various levels of judiciary and the risk has started to shift away from binary litigation risk toward collection and enforcement risk (Burford’s investment in the ‘Petersen claim’ is a great example of this phenomenon).

Needless to say, litigation is not a formulaic science and because of the large degree of human interaction and case complexity it will be relegated into the “arts” category for the time being. Perhaps artificial intelligence can help add a scientific element to determining value and litigation outcomes, but until the vast knowledge of settlement data becomes publicly available the industry will depend on ‘gut instinct’ and litigation experience in making its litigation decisions. From an investment perspective, the important point is that diversification is critical to capture the upside inherent in the asset class while minimizing the downside inherent in the inevitable losses that will be experienced.

Important Considerations

Other important factors to consider are the use of contingent fee arrangements and litigation finance and the impact those characteristics will have on the ultimate value of a piece of litigation. Some in the litigation finance community will argue that they will only consider providing financing to cases where the lawyer is providing their services on a 100% contingent basis (there could be jurisdiction specific constraints to the use of contingent fee arrangements), as this fosters great alignment between the plaintiff and the lawyer to maximize the value of the claim. Certainly the alignment argument makes intuitive sense. However, not every funder is convinced of this fact and, unfortunately, there is not a broad set of data that is definitive in this regard. Accordingly, until the data determines there is a strong correlation between contingent fee arrangements and outcomes, it remains to be seen. One funder on a panel of the September 2019 LF Dealmakers conference stated that their empirical data suggested there was not a correlation and hence it is not a significant feature to their underwriting process. Although, many funders feel strongly that the alignment argument is strong and they refuse to invest in a case where there is not some level of legal counsel fee contingency.

Then there is the existence and use of litigation funding itself. One could argue that the very existence of a plaintiff’s use of a litigation funder to pursue its case will shift the balance of power and ‘level the playing field’ between the plaintiff and the defendant, especially in a David v. Goliath situation where the defendant is ‘deep pocketed’ and the plaintiff relatively impecunious. As an investor in the industry, not only do I subscribe to the theory, I have seen the results. While many would suggest it is difficult to parse the effect of litigation funding from the effect of good legal representation and a meritorious claim, I look at the results of relatively small financings and I can see a correlation between success and short duration that I can, in large part, ascribe to the existence of litigation finance.

Investor Insights

As a consequence of the above, when I review track records for fund managers one of the metrics I look at is how often the realized outcomes are dependent on a judicial decision (bench, trial or arbitral) as compared to an outcome determined through settlement. Overall, the data concerning litigation outcomes illustrates that a high percentage of cases (90%+) are settled prior to a judicial decision and so we need to view the results in the context of industry settlement rates. Generally speaking, and depending on the case type and jurisdiction, I have a strong preference for fund managers that have a disproportionate number of settlements in their realized portfolios as opposed to outcomes that were derived from a judicial decision, given the binary nature of those outcomes. In certain jurisdictions, litigation funders are able to have some influence on the settlement discussions which may tend to favour higher settlement rates, so this issue and my approach to it is not identical in every jurisdiction. Another influencing factor on settlement rates is case types and case sizes. Generally speaking, I have noticed that outcomes dependent on judicial/arbitral decisions are correlated with larger cases and certain case types (As an example, International Arbitration cases would be one area where settlement is less likely and hence arbitral outcomes more prevalent).